We chuck out 31% of our food supply: How to stop the waste

How the pursuit of perfect, fresh food is feeding landfills—not people

CNBC.com

Food statistics can have a way of zeroing in on our collective eatingZeitgeist with uncomfortable data points. For example, U.S. consumers waste up to 50 percent more food than Americans did in the 1970s, according to National Institutes of Health.

And if you're assuming restaurants and farming are the sole culprits of food and agricultural waste, consider that a U.S. family of four discards around $1,500 a year on food, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Decades ago, fresh food was less desirable, and even perceived as dangerous. You reached for a salted piece of fish or meat. Frozen food wasn't a pariah. Over the years, fresh food has become widely available and almost idealized objects — proof of better eating and living than prior generations. From kale to quinoa, a grain high in protein, it seems every crop wants to be the next big, super food hero.

"There is this whole idealization of fresh food," said James McWilliams, a history professor at Texas State University at San Marcos and author of "Just Food," which tackles how to eat responsibly.

And hunting for the freshest can easily turn into a game of what's the best-looking produce. A priority on food aesthetics in turn creates a chain reaction in the food-supply system. Blemished items can end up in landfills, which create greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to global warming.

Only the best specimens make the cut onto U.S. and global food shelves. "A lot of product is excluded earlier in the supply chain because not everything grows that perfectly," said Dana Gunders, a scientist focused on food and agriculture for the Natural Resources Defense Council.

This desire for fresh, perfect food and the economics of farming are generating food and agricultural rubbish like never before. Producers sometimes throw out edible food because harvesting amid variable factors, like labor costs, can make processing unprofitable.

In California, the nation's largest agricultural producer and exporter, 25 percent of all state landfill waste is food and agricultural waste, according to the University of California, Davis.

And speaking of landfills, Whole Foods got dinged by a Twitter user for selling pre-peeled oranges in small, plastic containers. The retailer apologized and pulled the products. Oranges will be left alone in their natural packaging: Peels.

Of course food insecurity and poverty are real problems in America. But that's part of a much bigger set of global, agriculture-related challenges. Globally, populations and food demand are forecast to grow, giving new urgency to food waste reduction goals. The world's population will reach 9.7 billion by 2050, up from the current 7.3 billion, according to United Nations figures.

Scientists and researchers are seeking waste reduction, including technology-based solutions to transform food and agricultural waste into converted energy.

The end game is feeding people. Not landfills.

Peter Dazeley | Getty Images

Food in the garbage

"Our whole food system is based on maximizing profit. It's not based on maximizing food use."-Dana Gunders, scientist, Natural Resources Defense Council

The downside of abundance

U.S. food loss and waste accounts for about 31 percent of the overall food supply available to retailers and consumers, with far-reaching effects on food security and climate change, according to the USDA. Food loss and waste is single largest component of disposed U.S. municipal solid waste.

With the need for solutions accelerating, the U.S. in 2015 issued its first-ever national food waste reduction goal, calling for a 50 percent cut by 2030. The solutions lie in public-private partnerships as well as individual changes in eating habits.

In part because of the abundance of food choices and retailers, it's easy for consumers to chuck an edible head of romaine or hunk of cheese if they show only the slightest blemishes.

"The irony is that when people are in stores, they're so price sensitive. Ten cents will push them one way or another," said Gunders, also author of the "Waste-Free Kitchen Handbook" The book is a practical guide to preserving the shelf life of products, wasting less food and saving money. "Nobody wants to waste food," she said.

On the flip side, some in the food industry are exalting the qualities of imperfect or ugly foods to help solve world hunger. And there's more discussion about food expiration, and the difference between "sell by" and "use by" dates on packaging. "Expired" food doesn't necessarily have to be thrown away.

Last year, Doug Rauch, the former president of Trader Joe's, opened anonprofit grocery store in the low- to middle-income neighborhood of Dorchester in Boston. The shelves feature surplus and aging food.

"We can offer these daily values by working with a large network of growers, supermarkets, manufacturers, and other suppliers who donate their excess, healthy food to us, or provide us with special buying opportunities," according to the Daily Table store. And creative food sourcing business models can help feed America's working poor.

"Our whole food system is based on maximizing profit. It's not based on maximizing food use," said Gunders.

Building solutions

Source: University of California Davis

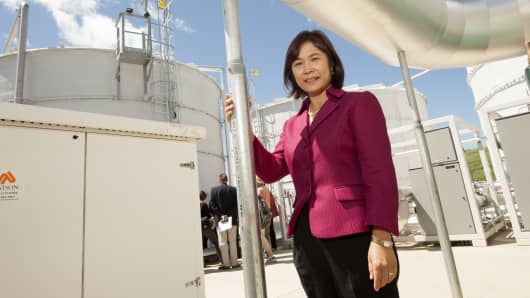

UC Davis researcher Ruihong Zhang has created technology that turns organic food waste, captured in the white tanks, into renewable energy generation.

Ruihong Zhang, a professor in UC Davis' biological and agricultural engineering department, invented the technology behind a commercial-grade, patented "BioDigester." It's designed to transform organic waste including food, yard and paper waste into biogas, which is then combusted to generate electricity and heat. Biogas can even be processed into renewable natural gas and transportation fuel.

This scientific process is called anaerobic digestion and includes a series of biological processes in which microorganisms break down biodegradable material in the absence of oxygen. Waste is stored in large, oxygen-free tanks (called digesters) with microbes.

The idea is farm to fork to fuel.

One BioDigester on the UC Davis campus can transform about 50 tons of organic waste daily to generate roughly 16,500 kilowatt hours of electricity a day. The wastes comes from multiple sources, including campus dining halls, restaurants and grocery stores.

There's a larger BioDigester in Sacramento in which 100 tons of organic waste (mostly food waste) is transformed into compressed renewable natural gas for fueling buses and trucks. Sacramento also has a smaller BioDigester, which takes in about 10 tons of waste per day.

"Agricultural waste is a big stream. But we can convert the waste to energy," Zhang said.

No comments:

Post a Comment