Aldi and Lidl grow despite ignoring the internet

It hasn’t stopped the discount grocers from thriving

THE aisles are wide, the lights bright and shelves low. Most obviously, however, the apples shine and the broccoli beckons. For those used to the cramped, dimly lit Aldi stores of yore, all expense spared, the new supermarket in Herten, Germany, is almost shocking.

Opened in April this is the prototype for a vast new renovation and expansion programme across Europe, Britain and America. It is the discount giant’s big bet on the future of shopping, all the more daring as the money is going almost entirely on bricks and mortar. Defying the conventional wisdom that customers want both in-store and online shopping (“omnichannel” in the jargon) Aldi wants to conquer the retail world by ignoring the internet. As too, to a lesser extent, does its great German rival Lidl. Plenty of other grocers reckon this may be the miscalculation that eventually brings them down.

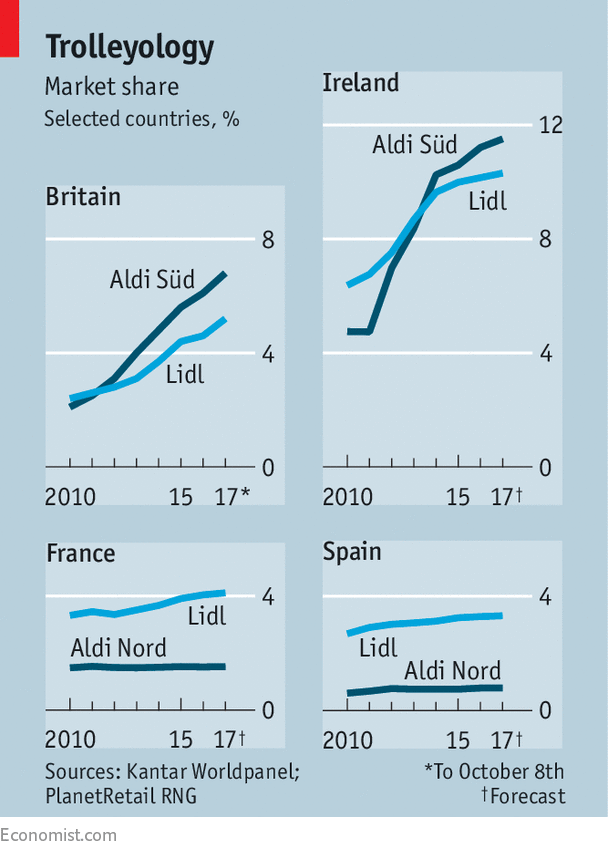

Founded in 1945 and 1973 respectively, Aldi (split into two legally separate companies, Aldi Nord and Aldi Süd) and Lidl have been eating up the competition, especially since the financial crash of 2008. In the cut-throat British market, Aldi (owned by Süd) increased its groceries share to 6.8%, from 6.2% just a year ago; Lidl’s jumped from 4.6% to 5.2% (see chart). At home in Germany, Aldi Nord’s market share has reached 12.9%, and Lidl’s 8.9%.

However, Aldi acknowledges that it must change to keep growing at this pace. Kay Rueschoff, Aldi Nord’s director of marketing, concedes that low prices, the discounters’ hallmark, are no longer enough. To lure middle-class shoppers, Aldi has to focus on quality, too—hence the shiny store in Herten. In all, Aldi Nord is spending €5.2bn ($6.1bn) on revamping its 4,800 stores in Europe (excluding Britain and Ireland) and opening hundreds of new ones. Besides ambient interiors, there is more fruit, veg and wine.

In Britain, Aldi Süd is unveiling about 70 new stores a year, often in impeccably middle-class areas that were once the preserve of posher British rivals such as Sainsbury’s. Aldi plans to open 900 swanky new stores in America, putting it third in the country by store count, behind Walmart and Kroger. (Lidl has just begun operating in America, and aims to have 100 stores within the year.)

Mr Rueschoff bristles at any suggestion that Aldi is changing too much. The new stores still sell only about 1,400 items, as opposed to the 50,000 or so on many rivals’ shelves, enabling big economies of scale. At Lidl, a new generation of senior managers last year began to upgrade their stores in a similar way. They resigned in February after their effort to expand Lidl’s small online offering was deemed too radical a departure from the discounter’s original, tight-fisted formula. But the idea that opening revamped stores as rapidly as possible is the best way to win market share, as well as make money, remains.

The discounters reason that whereas their conventional rivals, such as Sainsbury’s, might be able to win some customers online, they will not make much money out of it. Take Britain, one of the most advanced places in the world for e-commerce. Britons buy 7.3% of their groceries online, up from 6.7% a year ago, second only to South Koreans. Tesco, Sainsbury’s and others have spent hundreds of millions of pounds on sophisticated internet operations. Yet, as Bryan Roberts, an analyst at TCC Global, a consultancy, argues, these stores are merely “cannibalising themselves”, driving most of their shoppers from their most profitable channel (the store) to the least profitable (online).

Operating margins in the supermarket business are notoriously low, but even lower online, says Mr Roberts—about 3% versus 0.5% or less. Fleets of vans and drivers are expensive, but, argues Walter Blackwood, a consultant, supermarkets dare not charge cost price (or more) for the service as customers expect it to be virtually free. He attributes this in part to the baleful effect of the online behemoth Amazon, which does not seek to profit from the actual delivery of goods, thus creating the conviction that deliveries should be free. Customers expect the same from everybody else.

For the moment, Aldi’s decision to spend its money on physical stores is working. In less developed e-commerce markets, like America, they may have even more of an advantage. But the proportion of people shopping online can only go one way, so the strategy carries risks. Supermarkets are learning to make online sales more profitable, through “click and collect” schemes, for example, or raising the minimum transaction value for deliveries. A decisive clash of competing retail philosophies looms. To the victor, arugula. To the loser, turnips.

No comments:

Post a Comment