Relentless.com

At 20 Amazon is bulking up. It is not—yet—slowing down

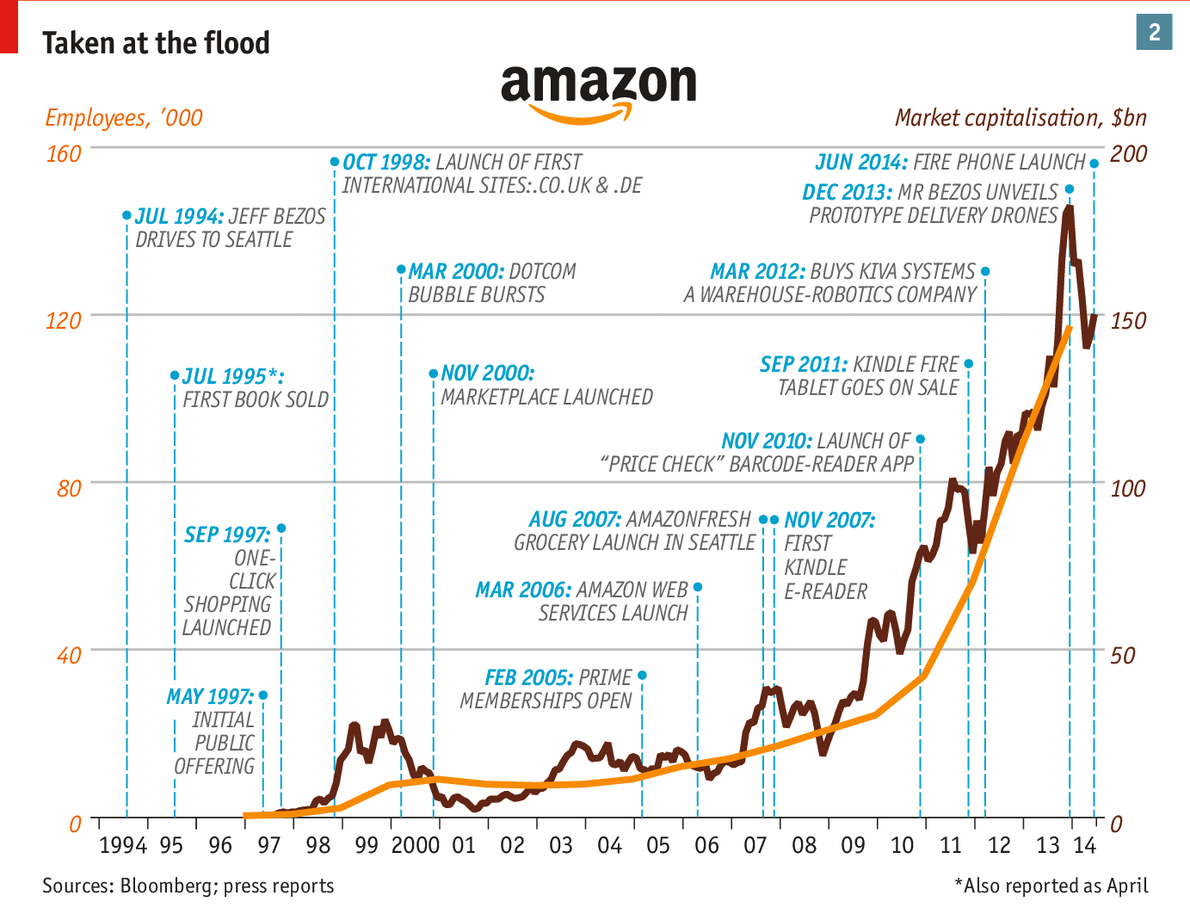

HIGH-TECH creation myths are expected to start with a garage. Amazon, impatient with ordinary from the outset, began with a road trip. In the summer of 1994 Jeff Bezos quit his job on Wall Street, flew to Fort Worth, Texas, with his wife MacKenzie and hired a car. While MacKenzie drove them towards the Pacific Northwest, Jeff sketched out a plan to set up a catalogue retailing business that would exploit the infant internet. The garage came later, in a suburb of Seattle, where he set up an office furnished with desks made from wooden doors. About a year later, Amazon sold its first book.

The world saw a website selling books and assumed that Amazon was, and always would be, an online bookshop. Mr Bezos, though, had bigger plans. Books were a good way into online retailing: once people learned to buy books online they would buy more and more other stuff, too. The website would be able to capture much more data about what they looked at and thus might want than any normal shop; if they reviewed things, that would enrich the experience for other shoppers. He saw a virtuous circle whereby low prices pulled in customers and merchants, which boosted volumes, which led to ever lower prices—a “flywheel” that would generate growth for as long as the company put the interests of the customers first. Early on, Mr Bezos registered “relentless.com” as a possible name; if it was a little lacking in touchy-feeliness, it captured the ambition nicely.

A phone to shop with

The latest manifestation of that ambition was unveiled in Seattle on June 18th: Amazon’s first phone. The Fire Phone is designed to stand out in a market crowded with sleek devices in various ways, such as with a sort-of-3D screen, but none is more telling than its Firefly button. This uses cloud computing to provide the user with information about more or less anything the phone sees or hears, be it a song, a television show, a bottle of wine or a child’s toy—including how to buy it from Amazon. If it works as promised, it will turn the whole world into a shop window.

The Fire Phone takes pride of place in an expanding family of devices with which Amazon has both anticipated and responded to shifts in the way consumers read, shop and divert themselves. Offering iPad-like tablets, e-readers and a television set-top box for streaming videos has brought the company into more direct competition than ever before with Apple and Google, which also offer suites of hardware, digital content and services. Amazon’s hope is that its signature selling points—features and quality that belie their relatively low pricing—will attract consumers to its devices just as they have to its online shops. Then they will end up shopping for other stuff, too.

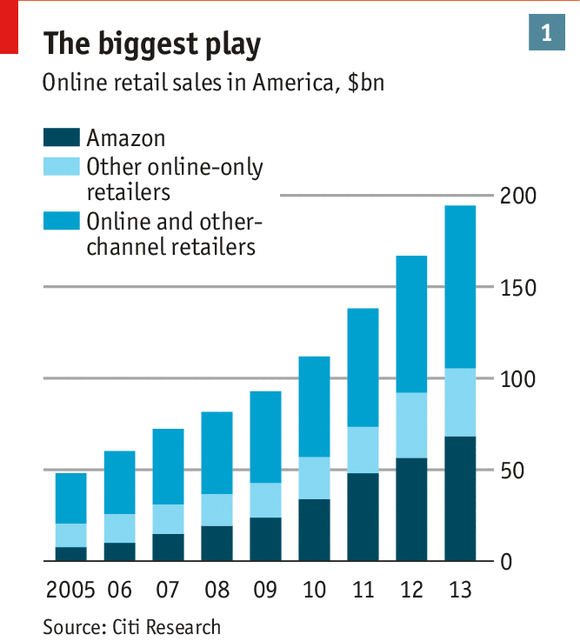

There is a lot of other stuff for them to buy. According to Internet Retailer, a magazine, Amazon now carries 230m items for sale in America—some 30 times the number sold by Walmart, the world’s biggest retailer, which has its own fast-growing online business—and there is no sign of let-up. Amazon’s total revenues were $74.5 billion last year, but when one takes into account the merchandise that other companies sell through its “marketplace” service the sales volume is nearly double that. Though by far the biggest online retailer in America, it is still growing faster than the 17% pace of e-commerce as a whole (see chart 1). It is the top online seller in Europe and Japan, too, and has designs on China’s vast market. Last year Amazon was the world’s ninth-biggest retailer ranked by sales; by 2018 it will be number two, predicts Kantar Retail, a research group.

On top of its online-retail success, Amazon has produced two other transformative businesses. The Kindle e-reader pioneered the shift from paper books to electronic ones, creating a market that now accounts for more than a tenth of spending on books in America and which Amazon dominates. Less visible but just as transformative is Amazon’s invention in 2006 of cloud-computing as a pay-as-you-go service, now a $9 billion market. That venture, called Amazon Web Services (AWS), has slashed the technology costs of starting an enterprise or running an existing one.

And Amazon enjoys an advantage most would-be competitors must envy: remarkably patient shareholders. The company made a net profit of just $274m last year, a minuscule sum in relation to its revenues and its $154-billion value on the stockmarket. Even after a recent slump (see chart 2) its shares still cost more than 500 times last year’s earnings, 34 times the multiple for Walmart. Its core retail business is thought to do little better than break-even; most of its profits come from the independent vendors who sell through Amazon’s marketplace. Matthew Yglesias, a blogger, memorably described Amazon as a “charitable organisation being run by elements of the investment community for the benefit of consumers.”

The company’s ascent has left a trail of enemies and sceptics, including competitors crushed—or forced to sell out to Amazon—by its ruthless pricing practices. It has been attacked for driving workers at warehouses too hard and of avoiding tax in America, Britain, France and Germany. The French culture minister has accused it of “destroying bookshops”. To Stephen Colbert, a comedian whose publisher, Hachette, is warring with Amazon over pricing, Mr Bezos is “Lord Bezomort”.

Amazon is sometimes a bully, but it does not yet threaten competition the way that its Seattle neighbour Microsoft did when it enjoyed a near-monopoly of operating systems for PCs. For every shop it obliterates another finds itself selling to places it never imagined it could. Ward Gahan, who runs BiddyMurphy.com out of an Irish gift shop in South Haven, Michigan, marvels that through Amazon he is shipping tweed caps to São Paulo. And Amazon’s success means that competitors are keenly plotting ways to best the company. “We wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for Amazon,” says Tom Allason, founder of Shutl, which uses local courier networks to deliver packages from retailers even faster than Amazon can. It was bought by eBay, an Amazon rival, late last year.

Get your kicks on PHX 6

Among the things that Amazon relies on to keep ahead of such competitors are Mr Bezos and the culture he has created. Though like many billionaires he has developed outside interests—he has a firm building a spaceship and owns a newspaper, the Washington Post—he still dominates the company, and has made invention, long-term thinking and viewing the world through the customer’s eyes its catechism. An almost perverse pleasure in low margins inspires ventures no one else would think of, like AWS. The building names on the Seattle campus drive the message home: “Day 1 North” reminds employees not to be complacent, but always to act as if just starting out; “Wainwright” is named after the first person to buy a book through the site. The bulldozer is an obsessive curator of its own traditions.

Mr Bezos is a notoriously testy boss, but also an inspiring one for the right sort of person. “He challenged me to create something like no one else challenged me,” says Vikas Gupta, who built Amazon’s payments software and now runs a startup. But the strengths the culture may offer are accompanied by a touchy, tight-lipped side that makes Amazon difficult to understand or to love. Amazonians will not tell visitors to its campus exactly where Mr Bezos works. They chatter freely about the consumer benefits of the firm’s devices and services but say as little as possible about the commercial logic behind them. The attitude is “everything we don’t talk about is a competitive edge,” says Mr Gupta.

Another huge Amazon advantage is a global network of 96 “fulfilment centres”, warehouses both vast and clever that shuffle shipments from thousands of suppliers to millions of customers. PHX 6, one of four such centres in Phoenix, Arizona, is a conveyor-belted Grand Canyon with a roof. With 11 hectares of floor space it could easily hold 20 American-football fields. A slogan over the door reads, a bit creepily, “Work hard. Have fun. Make history.” Inside, “stowers” scurry about with yellow containers placing items seemingly at random on shelves—board games abut power tools—and recording their location with pistol-like scanners. “Pickers” wield pistols that guide them on the shortest path through the jumble, measure their progress and log in the items they pluck from the shelves. Amazon’s plan to deploy thousands of robots in its fulfilment centres will shorten the pickers’ journey (and perhaps, in the long run, their careers). Through algorithmic alchemy, orders are packed into right-sized boxes, stamped with address labels and hauled away by couriers from UPS, FedEx and others.

Not all the stuff in PHX 6 is Amazon’s. “Fulfilment by Amazon” (FBA) allows independent merchants not just to sell their wares on Amazon’s website but also to ship them through Amazon’s supply chain. This helps the distribution centres pay their way. It also binds the merchants more closely to Amazon. Sellers tracked by Mercent, an e-commerce software company, use FBA for 16% of their sales, up from 8% in 2012.

Amazon’s original idea was to have few warehouses and to put them far away from population centres, thus avoiding the need to collect sales tax in the states with the most business. Now it is positioning infrastructure like siege equipment near big cities, speeding delivery and cutting its costs. In North America Amazon can offer same-day delivery to 23% of the population, says Marc Wulfraat of MWPVL International, a supply-chain consultancy. By 2015 it will be 28%. Spending on fulfilment centres in Europe and Asia as well as America tripled between 2010 and 2013, says Colin Sebastian of Baird, an investment bank. In Britain and parts of America Amazon has been experimenting with making last-mile deliveries itself, a practice that may expand along with its logistic network.

Following the Prime directive

The company sees ample opportunity for putting this infrastructure to work. Digital natives are entering their prime shopping years. When Walmart, with a poorer clientele, sells almost three times as much to its average American customer every year as Amazon does to its, there is plenty of room for Amazon to grow further.

One way to narrow the gap is to sell more “consumables”, such as toiletries and food. These account for nearly half of spending by internet-connected American households, but are thought to be a much smaller share of Amazon’s sales. Sanford C. Bernstein, a research firm, thinks its potential American market for non-perishables is $150 billion.

Then there is Prime, the flypaper on Amazon’s flywheel. Some 25m subscribers pay an annual flat fee ($99 in America, £79 in Britain) to belong to this souped-up loyalty programme, which offers shipping at no extra cost as well as increasing amounts of digital content. Scot Wingo of ChannelAdvisor, a company that helps online sellers, reckons that people with Prime spend around four times what others do and account for half of all spending at Amazon.

Many Amazon activities that look tangential to shopping have been designed to make Prime even stickier. In April it paid HBO, a television company, an estimated $200m-250m for a package of shows which Prime members can stream at no extra cost. On June 12th it added more than a million songs. Amazon produces programming of its own for the Prime audience, including several kids’ shows (mothers are good customers). If they own Kindle e-readers or tablets members can “borrow” a book a month. A slow reader need never pay for one.

And Amazon is very keen that they should own such devices. The shift from desktop to mobile shopping is a “big second wind to the whole of e-commerce,” says Sebastian Gunningham, the head of Amazon’s marketplace, and its devices are intended to catch as much as possible of that wind.

From the original Kindle, on which you could buy e-books, it moved to the Kindle Fire tablet, on which you could buy anything, and now the Fire Phone. As with every phone and tablet, the user can download apps from all sorts of other people, though those of Amazon’s rivals look under-represented. The gadgets do pretty much anything that phones or tablets from Apple or Samsung do, and have nifty wrinkles—such as a direct video link to technical support, on the Fire and the Fire Phone—which others lack. They are also pretty cheap—Amazon does not propose to turn a profit on them. It does, though, integrate them thoroughly into its other services, making them little wardrobes that open out into the Narnia of everything it has to offer. The Fire Phone comes with a year’s free Prime membership, encouraging people to become accustomed to Amazon’s streaming—and its free deliveries.

Outside the realm of e-books, Amazon has yet to make a great impression in the world of devices. Tablets from Apple and Samsung easily outsell the Kindle Fire—perhaps because, unusually for an Amazon emporium, its app store offers a smaller selection than do the others. “We struggle with whether hardware and streaming media will have value long-term,” says Eric Sheridan, an analyst at UBS. But the feature-packed Fire Phone shows that Amazon is not giving up. As Eric Best of Mercent says, “the battle for the shopper will be won on the phone”; Amazon thinks owning a bit of that battleground matters.

Amazon’s competitors are increasingly turning all sorts of devices into windows that display the wares of all sorts of other shops. Google sells mobile “local inventory ads” which point shoppers to nearby stores—an online-retailing option that avoids the need for fulfilment centres and delivery vans. It has enriched search results for shoppers with Amazon-like images and prices. Mr Best says he has noticed a slowdown in the growth of Amazon’s marketplace sales since Google became more active in selling stuff; Amazon claims not to see any such trend.

Turkish delight, too

Whereas some see Google as Amazon’s biggest worry, others tout Walmart, which has e-commerce sales that are growing faster than Amazon’s. Then there is Alibaba, a Chinese e-commerce giant soon to receive an infusion of cash through a share offering. It is planning a marketplace in America called 11 Main and is part-owner of ShopRunner, which promises two-day delivery from 100 retailers. A new wave of online-only shops like Wanelo (“Want, need, love.”) could pose a challenge. Or perhaps the threat will come from firms like Instacart, which lets people make deliveries in their spare time.

Mr Bezos has always insisted that Amazon will continue to be “customer-focused” rather than “competitor-focused”. In the letter he sent to shareholders when Amazon went public in 1997—and has had republished every year since—Mr Bezos warned that because of this focus the company would take a long-term view. If you ask Amazon officials about ventures that appear not to be prospering, like its push into Alibaba’s Chinese home base, they echo the boss. “We thought it would take us five years” to succeed there, says Diego Piacentini, the international chief. “We’ve figured out it will take us 15.”

But long-termism takes investment. In its early days Amazon danced around retailers because its lack of stores made it “capital-light”. Its empire of warehouses and data centres changes that. Now its pitch to merchants and technologists is that it will build physical assets so that they don’t have to. Amazon still uses less capital than traditional retailers, observes Matt Nemer of Wells Fargo Securities. But it is no longer capital-light. The flywheel is ever heavier—but must spin as fast.

The focus on Amazon’s meagre profits, though, can exaggerate the impression that its shareholders are simply waiting for it to start releasing all the revenue made possible by the dominant position it has achieved. In the past five years it has produced $10 billion of free cashflow, a less distorted measure of profitability than net income, which was just $2.9 billion over the same period, says Mr Nemer. That is still not much for a company worth $154 billion on the stockmarket. But investors are counting on Amazon’s growth to increase it. If you look at Amazon’s share price in relation to its sales (including those through the marketplace) it looks like a bargain, according to a recent note by Wolfe Research, an equity-research firm.

And investors know Amazon’s managers share their interests. Shares are the main way Amazon pays top employees; the highest salary—Mr Piacentini’s—is $175,000. Though it may look bent on world domination, it often passes on ventures it thinks will not pay off, like moving into South Korea. “The cost to be a relevant e-commerce player would be too high,” says Mr Piacentini. AWS will be “way more global” than Amazon’s retail operation.

In a television interview last year Mr Bezos admitted that Amazon “will be disrupted one day”, though not, he hoped, during his lifetime. It is hard to imagine it happening soon. That is not because Amazon always makes the right bets. The skeleton of an Ice Age bear displayed in Seattle, which Mr Bezos bought on Amazon’s abortive auction website, commemorates the failure. But the bets he has placed on customers, patience, technology and scale appear to have paid off. And he has followed through on them relentlessly.

No comments:

Post a Comment