Kroger And The Emerging Threat To The Business

Disclosure: I am/we are long COST. (More...)

Summary

While Kroger is arguably the best grocer in North America, I believe this article fills an analytical gap that has focused primarily on publicly traded competitors.

Emerging competitor, Aldi, has a very unconventional, highly disruptive business model.

However, the U.S. grocery market is very different than Europe where Aldi has seen much of its success.

And a well-run grocer like Kroger could manage through Aldi's expansion.

Kroger (NYSE:KR) is arguably the best grocer in North America and perhaps one of the best in the world. Readers do not need me to argue that point any further. Since December, a total of 8 positive SA articles were written on Kroger on why it is still a good investment. The performance of this company has been remarkable: recent quarterly same-store sales results, ongoing margin improvements and an active consolidation strategy suggest momentum is strong and the runway is long.

Yet none of the articles written mentioned an emerging competitor that some have called The Best Grocer in America. Privately owned by Germany's Albrecht family, Aldi is one of the few retailers that have repeatedly succeeded outside its home market. Perhaps, only Costco (NASDAQ:COST) could lay claim to such an enviable track record.

This article will be divided into 4 sections: (1) Aldi in the U.S., (2) Aldi's unconventional business model (3) What Kroger is doing (4) Aldi's increasing relevance (5) a brief review of Aldi's success in the U.K., (6) Why the U.S. is different (and Kroger need not worry) and (7) Why I believe Aldi matters to Kroger investors.

I don't intend for the analysis to be alarmist - I have too much respect and admiration for Kroger. Instead, I hope it highlights some legitimate threats for Kroger and other domestic grocers in a balanced fashion. As always, I will forget things, so I welcome your thoughts in the comments section.

1. Aldi in the U.S.

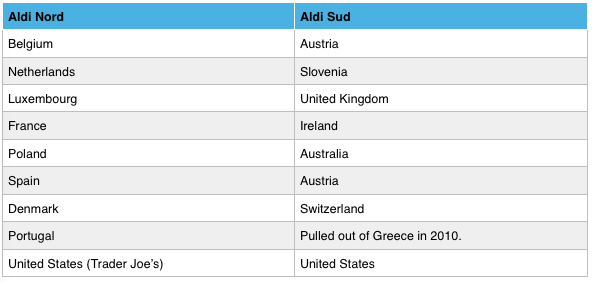

Aldi is one of the largest grocers in the world and is divided into two entities: Aldi Nord and Aldi Sud. After a family split, the company split into two separate entities and amicably divided Germany in half.

Later it seems they divided up Europe as well.

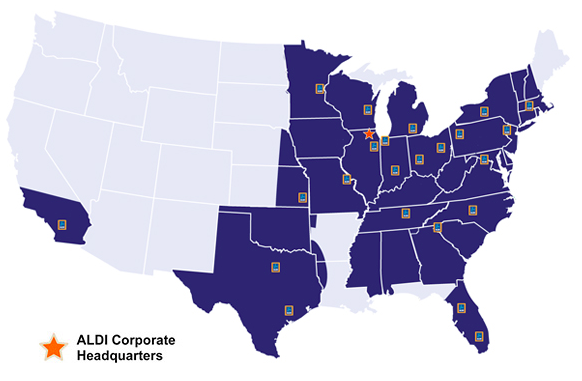

In the United States, however, Aldi Nord and Aldi Sud are direct competitors, and while they share similarities, operate separately. Nord acquired Trader Joe's (TJ's) in 1979 and is based out of California (where half of its stores are located) with more than 450 locations. Sud also entered the U.S. in the 70s and began a slow and methodical expansion. It now operates more than 1,400 stores across the U.S. and plans to boost that number to 2,000 by 2018, including an entry to TJ's backyard and the country's biggest grocery market, Southern California.

2. Aldi's unconventional business model

A typical Aldi is limited to 1,500 SKUs, which are mostly (80-90%) private label/store brands. National brands are included for price comparison or when they are highly coveted. Comparing the SKU count to the ~40,000 at a conventional grocer like Kroger or the ~100,000 at a hypermarket highlights how it is an insanely-focused offering. However, it comes with purpose.

The business is built on simplicity. The company intends to carry 90% of your weekly needs and forgetting the rest, which are often low-turning items. It also took the unconventional approach of offering customers fewer choicesinstead of trying to offer everything to everyone at a conventional grocer or hypermarket. So instead of choosing between say 40 types of peanut butter (size, brand, type, etc.), a customer has 4 choices. It makes the purchasing decision far simpler for the customer. I'd argue these ideas (simplicity, low SKU count) is more similar to Costco than any conventional grocer.

The narrow product offering leads to several benefits. First, store brands have allowed them to bypass wholesalers and purchase from suppliers directly. These lower product costs are passed on to consumers. Second, business complexity is reduced dramatically.

For example, staff only has to worry about ordering, stocking, merchandising, etc. a limited number of SKUs. As a result, efficiencies are found. Milk arrives already on racks so it can be restocked in seconds. Produce is often packaged together (or sold by unit) to speed up the checkout process. As a result, fewer staff is required to manage a store (~20) vs. more than 100 at a conventional grocer. Further, staff are required to do multiple jobs (as opposed to with working cash or in produce but not both). Customers also bag their own groceries.

Prepackaged Produce at Aldi

When purchasing from suppliers, the narrow product mix leads to greater buying power. Instead of spreading buying power over 40 different SKUs of peanut butter, it focuses it all on 4 SKUs. As a result, it often has more buying power on certain products than much larger competitors. The result is meaningfully lower prices.

It almost seems unbelievable. How can a retailer with less than 2% market share have more buying power than Kroger, with more than $100 billion in sales, or even Wal-Mart (NYSE:WMT)? However, it is true. A narrow product mix coupled with a simple supply chain, simple in-store experience and high mix of store brands is proving to be a winning formula.

"We can operate at a far lower margin because of our efficiency," says David Hills, Aldi's U.K. group buying director. "Everyone in our shops needs to do every job from mopping to check outs."

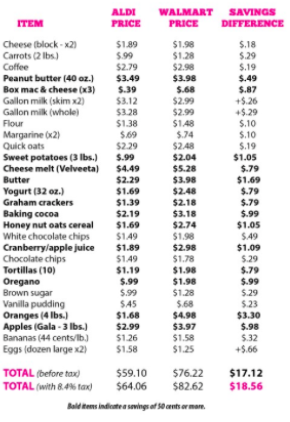

A well-reported studied done by Cheapism in 2014 found Aldi more than 15% cheaper than both Wal-Mart and Kroger:

In our price comparison the shopping cart tallies from late-February trips to one location of each chain in the Columbus, Ohio, area hit $72.30 at Aldi, $85.88 at Walmart, and $93.73 at Kroger. When accounting for savings available with the Kroger Plus Card, however, the supermarket's basket total dropped to $86.78, within one dollar of Walmart.

Another informal study found Aldi 20% cheaper than Wal-Mart.

The end goal is simple and focused: offer high quality products at low prices. As opposed to being everything for everyone, Aldi attempts to a) focus on shoppers who are willing to buy store brands to save money and b) meet the 90% of the needs of small basket, high frequency shoppers (with the remaining 10% bought through a bi-weekly trip to a big-box).

3. What Kroger is doing

Kroger does not yet seemed concerned with matching Aldi's pricing and instead remains focused being competitive with Wal-Mart. It is hard to argue with the strategy: each quarter, it continues to take share from industry leader Wal-Mart.

A. Consolidation: Kroger has a long runway for growth as a successful consolidator. The U.S. grocery industry is very fragmented, especially compared to other markets and will likely find plenty of smaller chains to purchase, similar to Roundy's.

It is worth noting that in Australia, the large supermarket chains, Coles (OTCPK:WFAFF) and Woolworths (OTCPK:WOLWF), haven't seen significant drops in profit despite Aldi's impressive growth in the country. While customers have benefited from lower prices, particularly when an Aldi opens nearby, the incumbents have managed to maintain margins by squeezing suppliers and boosting their private label offering despite having higher prices.

In contrast, Metcash (OTCPK:MCSHF) owned IGA and several independents have lost significant share, and in the case of Metcash, rapidly declining profit. This suggests the first (if any) impact from Aldi will be on independents and likely present further consolidation opportunities for Kroger.

B. Private Label: If anything, Kroger is already well prepared with a strong private label offering, including the country's largest organic brand, Simple Truth.

Kroger is expected to surpass Whole Foods to become the nation's top seller of organic and natural foods within two years, according to a recent report by JPMorgan Chase. Simple Truth, the company's natural and organic brand launched in 2012, is reportedly the largest organic brand in the country.

That said, the market for private label, while growing, remains less than 20% of grocery dollars. America still loves branded products, which somewhat limits Aldi's addressable market.

C. Clothing: Kroger continues to meet the needs of a broad segment of the population, such the addition of clothing. This is a little hard for me to understand as adding more general merchandise makes it more like a general merchandiser and dilutes management's focus on grocery retailing.

While a marginal addition, clothing (in my view) reflects a movement outside of its circle of competence (yes, despite Fred Meyer) and some desperation to keep same-store sales growth positive. In the short term, it may increase basket size but in the long run, it adds complexity - something that seems crazy when a well-run grocer like Aldi is expanding so quickly.

Kroger has dealt with Aldi for years and managed through it:

Take Aldi. It has been competing in Kroger markets for years. By moving into some other markets, it could make a difference in Kroger's share, Jim Hertel, managing partner at Barrington, Ill.-based food retail consultant Willard Bishop, told me."It siphons off a little business," he said. "It's meaningful, but it's not going to make a big impact. I suspect Kroger is certainly aware of them, but they're certainly not terrified."

But Aldi's increasing relevance amongst a broader range of consumers suggests it should, at least, be worried. Along with fresh format grocers, Limited Assortment retailers are forecast to see strong growth through 2018.

In accordance with its ongoing expansion plans, Aldi is and will continue to become more relevant to a broader range of consumers who've traditionally shopped at conventional grocers, like Kroger.

4. Aldi's Increasing Relevance

For Aldi, though, California could work well, as supermarkets in the state tend to be expensive while California has an older, low-income population that find the retailer's simple, midsize stores easy to navigate, said Bryan Gildenberg, head of research for Kantar Retail.

Aldi's announced $3 billion expansion plan intends to increase store count to 2,000 by 2018. If successful, this would give it a footprint comparable to the new Albertsons/ Safeway combination (2,200+) but still well behind Kroger (2,600+) and Wal-Mart (4,500+).

The expansion coincides with Aldi's evolution from a hard-discounter with limited fresh produce to one that meets the needs of more consumers, while maintaining its high-quality, low price advantage:

"Over the last 15 years Aldi has gone from attracting that income-constrained customer who needed to shop for the lowest-priced groceries, and evolved so that stores are more pleasant, more open and brighter. They've evolved merchandise assortments to be more trend-right. And that's widened the customer base from people who need to save money, to more of a smart shopper who wants to save money," Neil Stern, managing partner at McMillanDoolittle, told SN in an interview. "That's broadened Aldi's customer base and been a very good thing for them."

The company continues to add higher quality real estate in an environment where convenience is becoming more important to consumers. This shift, away from large weekly trips to the big-box in the suburbs, is giving small format retailers, like Aldi, a nice traffic tailwind. More and more consumers are choosing convenience:

"There was a generation of shoppers who were fairly comfortable with a long, weekly shopping trip," he said. "It was like the early days of America, with people going to market day once a week." But he said today's harried consumer wanted more convenience and to spend less time in the aisles."

With Aldi, the benefit is even better. Not only do consumers get convenience but they also get low prices - this is, as one author described, the rise of"discountvenience."

5. Experience in the U.K.

Nowhere can we learn more about the impact of Aldi's expansion than in the U.K. Much like in the U.S., the discount segment has grown and increased in relevance to a broader range of consumers in recent years. The impact has been significant:

The CEO of Asda, the UK's second-largest grocery chain, has called the new competitive environment created by Aldi and Lidl "the worst storm in retail history." "When we set the plan, I don't think anyone anticipated the market being in meltdown," Asda CEO Andy Clarke said in August after the Walmart-owned company reported its worst ever quarterly sales drop.

Amazingly, Aldi and Lidl (its German counterpart) have done it with just 10% share - a figure they doubled in 3 years. Previously, it took them nearly 10 years to double share.

Post the GFC, an increasingly larger amount of customers shopped at discounters. Aldi and Lidl took this opportunity to improve their offering and move up-market. Customers liked it and remained loyal. The market share of the top 5, which previously controlled 80% of grocery dollars, continues to decline while Aldi and Lidl's increases.

This chart shows how the shift, seemingly out of nowhere, accelerated:

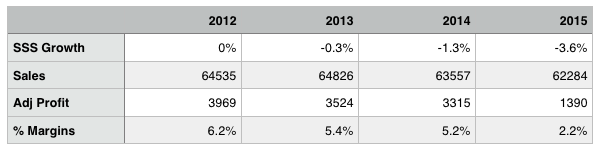

The larger impact has been on profits, which have, in some cases, fallen significantly as a result of price wars. Consider Tesco (OTCPK:TSCDF):

How did this happen? When volumes at the conventional chains slowed, they tried to raise price and increase margins to maintain earnings growth. This opened a gap for Aldi and Lidl and left the conventional players ill-prepared for the shift to discount.

Two important takeaways: first, Aldi can be a competitive nuisance to Kroger without a meaningful market share. Just the presence of a discount store can cause prices in a neighbourhood to fall. The top 5 in the U.K. still control more than 75% share, yet it's a nightmare. In the world of Aldi, market share and sales do not always equal profits. If Kroger is not laser focused on this threat, specifically maintaining price competitiveness, the results can be ugly.

Second, its impact can build like a snowball. As they become more accepted by customers, including high income earners, they can open higher quality real estate, which makes them more convenient to a broader population. The result? Market share and financial impact to incumbents accelerates to a point where it becomes meaningful.

6. Why the U.S. is different (and Kroger need not worry)

I'll elaborate on two characteristics of the U.S. market relative to the European markets Aldi has traditionally found success:

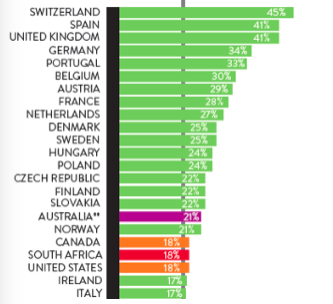

First, Europe has traditionally been far more accepting of private labels, especially Germany and the U.K where upwards of 40% of grocery dollars are spent on store brands. This arguably makes them more prepared and accepting of Aldi's private label offering. In the U.S., however, Aldi must convince a loyal national brand shopper to choose a store brand - a much harder proposition.

Second, concentration like the U.K. is typical in Europe. Many countries have large conventional grocers that dominate 80% or more of the market. In contrast, the U.S. is a far more fragmented, regional, and competitive market - to the point where reliable data is difficult to attain. Consider the fault in the following table - it excludes dollar stores, notably Dollar General (NYSE:DG), which has a large consumables offering as well as Aldi (estimated at 2% share).

Furthermore, one could argue that a retailer like Dollar General, with a simple, low-priced consumables offering at over 11,000 stores, has already filled part of Aldi's potential discount market - even more so with Dollar General Market.

Third, Kroger already felt and dealt with the impact of an everyday low price (EDLP) discounter. In the late 90s and early 2000s, it adjusted pricing, improved the loyalty program and emerged stronger than ever after being ill-prepared for Wal-Mart's earlier expansion. At just over 3%, Kroger's operating margins are far lower than Tesco's where, as recently as 2012, they were greater than 6%. The U.S. is a much more competitive market.

7. Final thoughts: Why it still matters to Kroger investors

I hope this article helps build awareness and discussion of an emerging threat to Kroger, Wal-Mart and other domestic grocers.

I first became interested in Aldi after learning of its similarities to Costco. It quickly became apparent that this company has developed a better mousetrap. In the U.S., as that mousetrap gains scale, opens better locations, and becomes more relevant to a broader income demographic, Aldi will have an impact. With a price advantage, not only will it continue to encroach on Wal-Mart's EDLP stronghold, but will also challenge traditional grocers, like Kroger.

Kroger's weaknesses lie in its complexity. Operating a simple, narrowly-focused business like Aldi is not in its DNA. And if it begins losing share, things can get ugly, quickly. Conventional grocers will always remain relevant, but with Aldi, they simply become less so and lose share. Even offering only 90% of what you need, Aldi has repeatedly proven that customers like the store, product offering, and easy shopping experience. With recent expansion plans, there is a risk that its impact on U.S. grocers accelerates.

Kroger's strengths lie in its ability to be a successful consolidator. If it can buy smaller, struggling operators, it gains more scale and buying power to stay reasonably close to Aldi's pricing. Management is certainly aware of the fact that fresh, limited, and discount formats are forecast to grow faster than conventional. Further, with national brands still preferred by U.S. consumers and Kroger's strong private label offering, any impact could remain more than manageable. Plus, with much lower margins than Tesco and previous experience with Wal-Mart, it's arguably better prepared.

No comments:

Post a Comment