A

world without water

In the first instalment of a series on the

threat of water scarcity, Pilita Clark reveals the cost to companies

JULY 14, 2014 7:25 PM

The River Nar, a minor waterway about 100 miles

north of London, is barely known to the average Briton. And at first glance, it

is hard to understand why a brand-conscious company such as Coca-Cola would want to have anything to

do with it.

Some of

the Nar bears an unhappy resemblance to a ditch, thanks to decades of

re-routing that have left it so straight and narrow its murky waters can be

crossed in a single step. Unlikely as it may seem in soggy Britain, it also

suffers from a lack of water because outdated licensing rules have allowed it

to become overused.

But the

river is significant to Coca-Cola because it flows through an area that

supplies a large chunk of the sugar beet the company uses to sweeten the drinks

it sells in the UK.Fertiliser run-off from farms has contributed to the Nar’s

troubles.

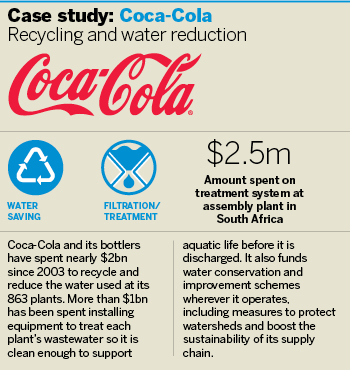

Coca-Cola

knows that these sorts of problems can pose a risk to its business. Eleven

years ago one of its bottling plants in India was subjected to angry protests

over its impact on local water supplies and eventually closed. It has long

insisted the accusations were unfair. But since 2003 Coca-Cola and its bottlers

have spent nearly $2bn to reduce their water use and improve water quality

wherever they operate. That spending now extends to a sodden field next to the

Nar, surrounded by clumps of stinging nettles and the odd goat, where the

company recently paid for something very unusual to be done to improve the

river. It gave £1.2m to the World Wildlife Fund conservation group, which has

dug a winding channel to restore a straight

stretch of the river back to a meandering version of its older, natural self. “It’s

definitely not your average conservation project,” says Rose O’Neill, WWF water

programme manager, explaining that the scheme and other related work Coca-Cola

has funded will help the river clean itself and tackle water scarcity.

Coke’s

nearly $2bn in investments may sound big but in fact they are a small example

of how much companies are starting to spend on water worldwide. Nearly 20 years

after the World Bank began warning of a looming water crisis, the combination

of a surging population, a growing global middle class and a changing climate

is straining water supplies. For companies – from multinational corporations to

small businesses – this amounts to higher costs for a resource that has long

been taken for granted.

“The

marginal cost of water is rising around the world,” says Christopher Gasson,

publisher of Global Water Intelligence. “Previously, water was treated as a

free raw material. Now, companies are realising it can damage their brand,

their credibility, their credit rating and their insurance costs. That applies

to a computer chipmaker and a food company as much as a power generator or a

petrochemicals company.”

Examples

of these costs abound:

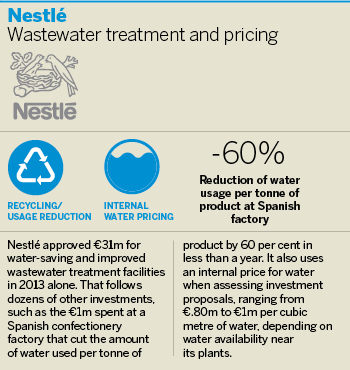

● Nestlé, one of the world’s biggest food

companies, set aside SFr38m ($43m) for water-saving and wastewater treatment

facilities at its plants last year.

● In

Australia a subsidiary of BG Group, the British oil and gas company, has

launched a A$1bn

($938.7m) water monitoring and management system that will pipe

treated water from its gasfields to boost water supplies for farmers and towns.

● Antero

Resources, a US shale gas company, plans to spend $525m on a pipeline to carry

water to its operations, boosting the reliability of its supplies.

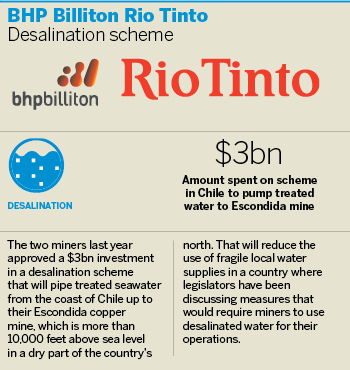

● Rio Tinto and BHP Billiton have launched a $3bn

desalination scheme in Chile that will pump treated seawater up 10,000ft to a

jointly owned copper mine, cutting their use of fragile local water supplies.

● Ford, the carmaker, has built a $2.5m water treatment system at its

Pretoria assembly plant in South Africa that is increasing water reuse up to 15

per cent. “We see it as definitely an emerging issue that we feel we need to

address,” says John Viera, global head of sustainability.

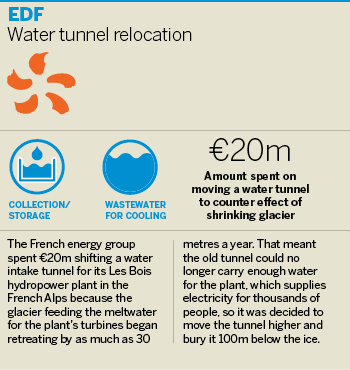

● EDF, the French energy group, has spent €20m

shifting a water intake tunnel for one of its hydropower plants in the French

Alps because the glacier feeding the meltwater for its turbines retreated so

much the old tunnel could no longer capture enough water. “Water management is

not only a developing country issue,” says Claude Nahon, the company’s head of

sustainable development.

Since

2011 companies have spent more than $84bn worldwide to improve the way they

conserve, manage or obtain water, according to data from Global Water

Intelligence, regulatory disclosures and executive interviews with the

Financial Times.

The

reasons for each investment differ. Some are driven by physical water

shortages, others by new industrial processes requiring water in greater

quantities or of higher quality. Other companies want to show customers they

care about water conservation. Some are motivated by new environmental

regulations requiring better wastewater treatment.

The $84bn

figure is neither comprehensive nor easy to compare with past spending levels.

This is because companies are generally not required to disclose capital or

operating costs for water-conservation measures. While some businesses

highlight water investments in their sustainability reports, relatively few

disclose the price of such schemes.

The bottom line

Google,

for example, declines to say how much it spent on a plant it has built at one

of itsdata centres in the US state of Georgia, which

enables it to use diverted sewer water to keep its servers cool. Nor has it

disclosed how much it spends at a Belgian data centre that uses water from an

industrial canal.

Previously, water

was treated as a free raw material. Now, companies are realising it can damage

their brand, their credibility, their credit rating and their insurance costs

- Christopher Gasson, Global Water Intelligence publisher

Joe Kava,

the company’s head of data centre operations, has warned that water is “the big

elephant in the room” for tech companies, which can typically use hundreds of

thousands of gallons of water a day. “We’ve been

focusing on power consumption and energy efficiency and that’s excellent,” he

said in 2009. “I think the next thing we need to turn our attention to is what

do we do about the looming water crisis?” As water becomes more scarce, data

companies’ use of it could attract public scrutiny, he added, possibly

resulting in regulations governing how much water they consume.

Google

told the FT last week that its focus on water conservation means it now has a

facility in Finland cooled entirely by seawater. It is also looking at using

captured rainwater in South Carolina.

Regulation

is a growing concern for many companies, which is a reason investors are

starting to press for more disclosure about water risks.

Norway’s huge $890bn oil fund, the world’s

biggest sovereign wealth fund, is one of several large investors urging

companies to improve their reporting. It cites what Jan Thomsen, its chief risk

officer, has described as “increasing water scarcity and

adverse water-related events” that could affect its long-term returns.

The fund

is one of 530 investors with $57tn in assets that work with the Carbon Disclosure Project,

an international environmental charity. On behalf of those investors, CDP asks

large companies each year to disclose the risks and opportunities water poses

for their business. Last year 70 per cent of the 180 FTSE Global 500 companies

that responded said water was a substantive risk to their business, up from 59

per cent in 2011.

A similar

trend has emerged in the most recent edition of the World Economic Forum’s

annual global risk

survey of business executives and other leaders. Water supply

crises were not rated among the five biggest concerns in terms of impact in any

year up to 2011, but have been among the top three listed every year since

2012.

Water

scarcity is no longer just a small, plant-level issue for companies but has

become a strategic question for senior management, says Martin Stuchtey of

McKinsey, the consultancy. “It’s capturing a larger part of the capital

expenditure bill at many companies,” he says. The $550bn global water market –

which covers everything from water treatment plants to pipelines – is expanding

at about 3.5 per cent a year, he adds. But it is growing much faster in some

industries: as high as 14 per cent a year for the oil and gas sector and 7 per

cent for the food and beverages industry.

Mining matters

Those

rising costs are most visible for one business sector: mining. The industry’s

spending on water has increased from $3.4bn in 2009 to nearly $10bn in 2013 and

is likely to exceed $12bn this year, according to Global Water Intelligence.

It says

BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto’s $3bn desalination scheme for their Escondida

copper mine in Chile was a record for an industry in which water infrastructure

has traditionally accounted for about 10 per cent of a mine’s cost, but has

recently reached as much as 30 per cent. At least seven other mining groups in

the country have drawn up plans for smaller desalination plants worth a

combined $1bn. Water scarcity is such a concern that Chilean legislators have

been discussing a measure requiring miners to desalinate their water instead of

drawing on local supplies.

More

plants are also planned for mines in neighbouring Peru, where the industry has

had its own version of Coca-Cola’s troubles in India: in 2011 the $1bn Tía

María copper mining project run by US-based Southern Copper was halted after violent

protests by farmers about its water use left three people dead. Other projects

have been dogged by similar troubles.

Nonetheless,

Rio Tinto, the junior partner in the Escondida mine, plays down suggestions

that water shortages are an unmanageable financial problem. “We haven’t felt it

as being a significant trend for the business, but it is a material risk that

we are managing,” said Matthew Bateson, Rio Tinto’s global head of environment.

Still,

some experts are less relaxed. “It’s plainly true that water scarcity is

finally starting to bite financially,” says Andrew Metcalf, an investment

analyst and author of a 2013 report for Moody’s, the credit rating agency, that

was among the first to warn of the financial impacts water shortages have begun

to pose for the mining industry.

Mr

Metcalf believes miners are not the only ones at risk. “Regulators in markets

where oil and gas groups, chemicals companies and others operate have massively

tightened the rules, and thus costs of compliance, regarding water usage in the

last three to five years,” he says. “In the past, companies could do a project

and spend more money on water if a problem later arose. Now, they have to have

a plan showing how they won’t affect local water supplies before they can start

operating.”

Costs are

likely to keep rising according to Mr Metcalf’s report, because 70 per cent of

the six biggest global miners’ existing mines are in countries where water

stress is rated as a high or moderate risk, along with two-thirds of projects

being developed.

The

result is “projects will take longer to complete, be costlier and riskier, with

credit-negative implications for the entire industry”.

Managing water scarcity

One

executive with little doubt about the rising costs of water is Peter Brabeck,

chairman of Nestlé. He has been at the forefront of corporate efforts to draw

attention to water scarcity, a problem he believes is still not taken as

seriously as it needs to be. “Humankind is running out of water at an alarming

pace,” he says. “We’re going to run out of water long before we run out of

oil.”

Water

scarcity is a far more pressing problem than climate change, he says, but

receives much less political attention than it should. “We have a water crisis

because we make wrong water-management decisions,” he says. “Climate change

will further affect the water situation but even if the climate wouldn’t

change, we have a water problem and this water problem is much more urgent.”

One

reason water receives less attention is that, unlike global warming, there is no

such thing as a global water crisis. Instead, there are a series of regional

predicaments in a world where the distribution of fresh water is so lopsided

that 60 per cent of it is found in just nine countries, including Brazil, the

US and Canada, according to the

UN.

Another

reason the problem persists, insists Mr Brabeck, is that water is so

undervalued that it is typically used inefficiently – and there is not enough

investment to boost supplies.

As the

chairman of a leading bottled water seller, whose brands include Perrier and

Poland Spring, he has drawn fire for this view from activists opposed to any

form of water privatisation. He also agrees the provision of water for drinking

and basic needs is a human right. Still, Nestlé has taken an unusual approach

to valuing water by introducing an internal “shadow price” for it that is used

by the company when assessing proposals to buy new equipment to improve the

efficiency of how water is used in its factories. The price is just over $1 per

cubic metre for sites where there is abundant water and about $5 in drier

spots.

Such a

move makes good business sense for a company such as Nestlé. Its coffee,

cereals and milk products sit on breakfast tables worldwide, meaning it has a

global reputation to protect. It is also the 49th-biggest industrial consumer

of water in the world, according to Global Water Intelligence.

That

makes it far more vulnerable to customer boycotts than the biggest water

consumer, China Guodian, a power generator, which has captive customers and is

barely known outside its own country.

That

vulnerability is one explanation for the water investments at many companies,

not least Coca-Cola, which ranks as the 24th-biggest industrial consumer of

water and is one of the world’s most recognisable brands. The closure of its

bottling plant in India galvanised awareness of water risk at many drinks

companies. “It was certainly something that had a lot of impact for us,” says

Greg Koch, Coca-Cola’s director of global water stewardship. He adds that it

showed the company needed an “emotional licence” to water, on top of regulatory

permission. “I don’t mean emotional in a perjorative sense, like emotional

baggage. I mean it in the sense that water is spiritual, it’s religious, it’s

visceral, it’s daily. Everyone has a first memory of water; you don’t have a

first memory of a carbon offset credit.”

Farms versus industry

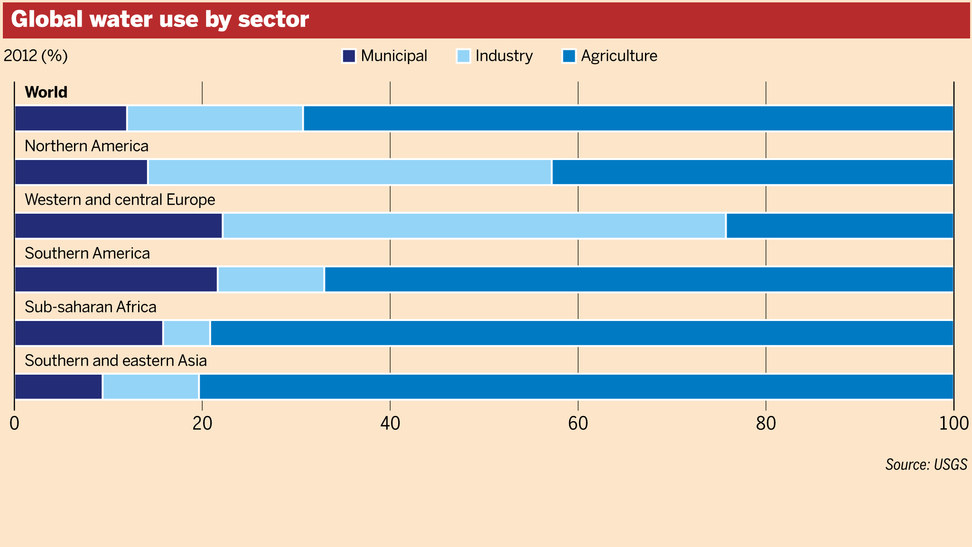

For all

the accusations of water hogging made against Coke or any other business,

however, industry comes a very distant second to the world’s biggest water

users: farmers.

Agriculture

accounts for 70 per cent of all water use compared with 22 per cent for

industry and just 8 per cent for domestic users, says the UN.

These

proportions vary by country but the problem water scarcity poses for businesses

in many parts of the world is that shortages pit the two biggest users, farmers

and factories, against each other.

In Iran,

farmers last year smashed a pipeline they said was diverting water to factories

in a nearby city. In Australia, farmers have formed a movement against coal

seam gas drilling they claim will damage water supplies. And in India, which

accounts for more than 30 per cent of the increase in global water withdrawals

over the past 15 years, farmer protests over water have been aimed at companies

ranging from coal-power generators to soft-drink makers. Another Coca-Cola

bottler, this time in the north of India, was temporarily closed last month

after local farmers complained about its water use.

The

number of water-related conflicts reported

worldwide has surged in the past 15 years, according to the Pacific Institute,

a water research group. US intelligence officials have also raised concerns

about the risk of conflict over water. “We assess that during the next 10

years, water problems will contribute to instability in states important to US

national security interests,” said a 2012 intelligence report prepared for the

US State Department.

That

report highlighted the risk to global food markets from the rapid depletion of

one crucial source: groundwater.

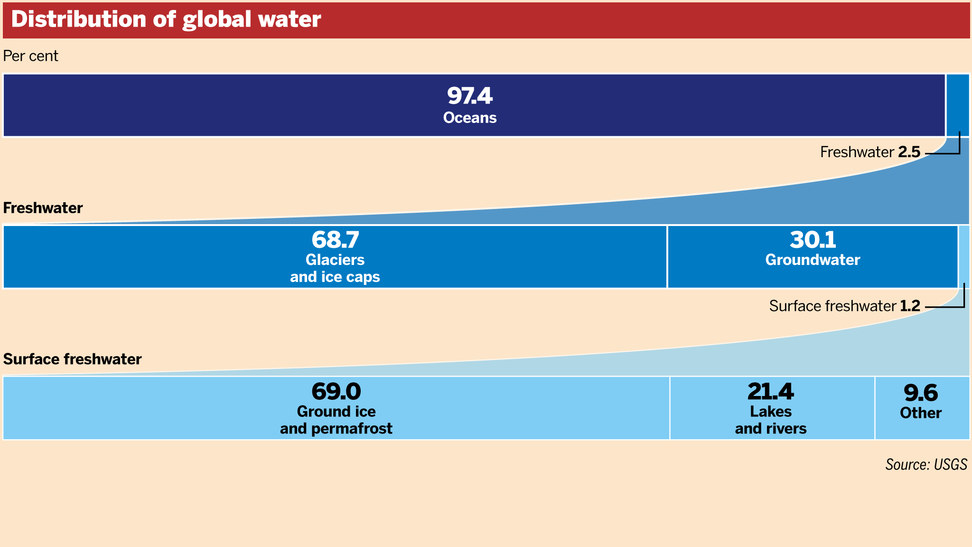

Just over 97 per cent of

the world’s water is in its oceans. Of the 2.5 per cent that is fresh water, almost

70 per cent is locked away in glaciers and ice caps and about 1 per cent

is in lakes, rivers and other surface water sources. The remaining 30 per cent

is groundwater, some of it so ancient and hard to replace it is known as fossil

water.

Drilling deep

Less than

a century ago relatively little groundwater was used. But as the global

population surged, driving up food demand, it led to a boom in extraction that

began in a few countries such as Spain and the US but has now spread worldwide.

An

estimated 2bn people rely on groundwater for drinking and irrigating crops but

its use is often unregulated and poorly monitored. This means more is pumped

out than can be replenished quickly when it rains.

In the US

groundwater levels around California’s Central Valley farming area have been

declining rapidly. Between 2003 and 2010, a volume of water almost equal to

that in the country’s largest reservoir, Lake Mead, was lost, according to a

study led by Jay Famiglietti of the University of California who uses Nasa

satellite data to monitor depletion.

In the

Middle East, countries including Iran and Syria lost an amount almost equal to

the Dead Sea over a similar period, mostly because of groundwater pumping.

But in

terms of the severity of the depletion, northwestern India is the worst, says

Prof Famiglietti. Water-hungry farms and rapid population growth mean that

between 2002 and 2008, the region’s aquifers lost an amount of water nearly

three times the maximum Lake Mead can hold.

Globally,

pumping out so much groundwater has contributed to a “small but not trivial”

increase in sea levels as the extracted water eventually makes its way to the

oceans, according to Leonard Konikow of the US Geological Survey, a leading

groundwater expert.

The politics of

agriculture are such that no politician is ever going to remove subsidies for

farmers, whether it’s in California or anywhere else

- Scott Rickards, Waterfund founder

At the

heart of the groundwater problem is a host of regulatory deficiencies that

companies alone can do little to change, including subsidised water for

impoverished farmers that governments are loath to touch. “The politics of

agriculture are such that no politician is ever going to remove subsidies for

farmers, whether it’s in California or anywhere else,” says Scott Rickards,

founder of the US Waterfund group, which develops financial risk-management

products for the water industry.

One

company acutely aware of the dilemma is SABMiller, one of the world’s biggest brewers.

It has paid millions of dollars to conserve and improve its own water supplies,

including $6m to upgrade pipes and other equipment at one of its plants in

Tanzania affected by deteriorating water quality. At another of its facilities

in the Indian state of Rajasthan, however, groundwater is disappearing so fast

it has become “quite a significant risk to the brewery”, says Andy Wales, the

company’s head of sustainable development.

SABMiller

has invested in several measures to boost supplies, and it replaces more water

than it draws out every year. Still, “that’s not enough to solve the problem

because the farmers are still using it”, he says, noting that irrigation water

is typically so cheap it is used inefficiently. SABMiller pays about 50c for

each cubic metre of water it uses in South Africa, for example, while the

farmers irrigating the barley used in its beer can pay half of 1 per cent of

that price for the same volume of water.

“The only

solution for companies really is to understand those local risks; dramatically

improve efficiency and engage with local communities, governments and others to

put in place projects that protect the watershed for all users.”

The cost

of such measures is unlikely to fall as the world’s population becomes bigger,

and richer.

·

Water scarcity is a

pressing issue for corporations, environmentalists and the world as a whole.

Just 2.5% of the planet’s water is freshwater. Not only is this important for

human and animal consumption, saline water is unusable for many industrial

purposes because of its corrosive properties.

·

Of that share, more than

two-thirds is locked up as ice – inaccessible for consumption by industry,

agriculture and humans.

Of the remainder, only a

quarter is readily available for use – or far less than 1% of the earth’s total

water resources.·

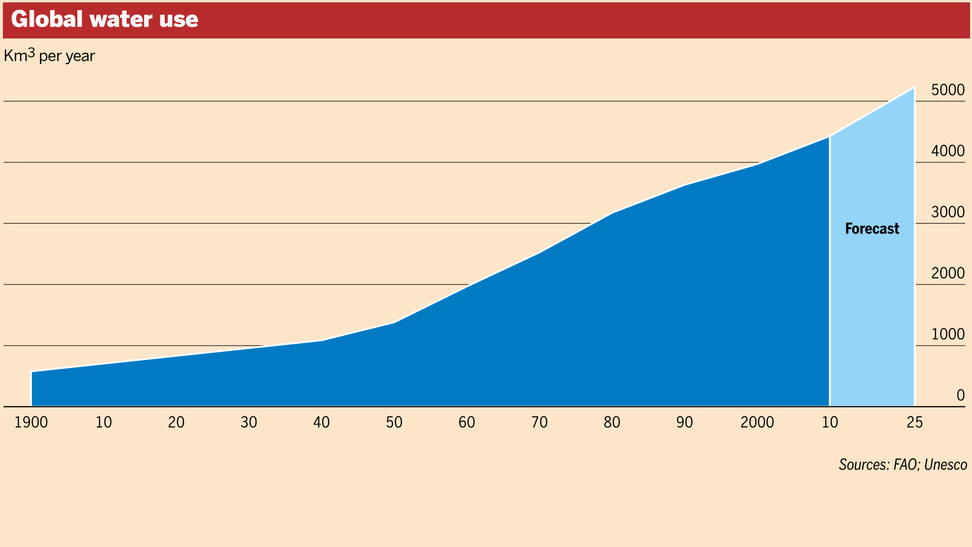

This situation is

exacerbated by soaring global water use, which grew almost eightfold between

1900 and 2010. Projections suggest no imminent slowdown in this trend.

This scarcity manifests differently in different

regions. Across the world as a whole, agriculture is the dominant sector for

water use, meaning scarcity endangers food security. In western and central

Europe, however, industry is under most pressure.

Energy shocks

By 2030,

the global population is expected to have increased from today’s 7bn to 8bn.

The global middle class, meanwhile, is likely to have surged from nearly 2bn to

5bn, according to the OECD, largely in fast-growing Asian economies. Like their

predecessors in developed countries, they are likely to want a hamburger, not

just a bowl of vegetables, and the UN has calculated it

takes 2,400 litres of water to produce a hamburger compared with less than 30

litres for a potato or a tomato. They will also want air-conditioning,

televisions and other devices requiring electricity, on top of family cars and

overseas holidays, all of which require more energy.

Water is

needed for almost every aspect of energy production, from digging up fossil

fuels to refining oil and generating power, and the amount of water consumed by

the sector is on track to double within the next 25 years, according to the

International Energy Agency.

In the

Middle East, Royal Dutch Shell and Qatar Petroleum

have built Pearl, the world’s biggest plant for converting gas to liquid fuels.

The Qatar plant includes a groundbreaking water recovery and treatment system

that Shell says eliminates the use of local water supplies. Shell declined to

divulge the price but Global Water Intelligence estimates it cost $640m.

Water is needed for almost every aspect of energy production,

from digging up fossil fuels to refining oil and generating power, and the

amount of water consumed by the sector is on track to double within the next 25 years

“It’s a

huge project,” says Laurent Auguste, director of innovation and markets at

Veolia, the French water services group, which helped design and build the

system. “It’s definitely something that you probably would not have thought of

years ago but something that is absolutely critical.”

Water

supplies are crucial for one of the energy industry’s most vibrant sectors: the

booming US shale industry. The hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, process used

to extract shale gas and oil typically requires about 2m gallons of water or

more at each well. That has prompted concern among groups such as Ceres, a

sustainable investor group,which says nearly

half the US wells drilled since 2011 are in areas of high or extremely high

water stress.

But the

shale industry is only one part of the energy sector confronting water

scarcity, says Tara Schmidt of Wood Mackenzie, the energy industry analyst.

“This is no longer a ‘could be’ issue, this is a forefront issue,” she says.

“Most energy companies definitely recognise they are under increasing scrutiny

from governments and the public about how they use their water supplies.”

The risk

is evident in China, where it has become mandatory in some regions for

coal-fired power plants to be cooled with air instead of water. Installing an

air-cooling system costs about $100m at an average-sized plant, say industry

analysts, and also reduces efficiency because the plant needs to burn more coal

to produce electricity to operate the system. This also produces more of the

carbon dioxide responsible for climate change, underlining the difficult

environmental trade-offs posed by the issue of water scarcity.

Desalination

is another way that water scarcity is inadvertently leading to greater use of

energy, thanks to the soaring increase in the number of plants that need

electricity to operate. Forty years ago there were hardly any desalination

plants. Today there are more than 17,200 producing a volume of water equal to

just over 21 years of rain in New York, says the International Desalination

Association.

Most energy

companies definitely recognise they are under increasing scrutiny from

governments and the public about how they use their water supplies

- Tara Schmidt, Wood Mackenzie

They are

no longer confined mostly to the deserts of the Middle East either. The top 10

countries, in terms of online desalination volume capacity, include Spain,

Australia and China, and companies are one reason why. Since 2010 45 per cent

of new plants have been ordered by industrial users such as power stations and

refineries, up from 27 per cent in the previous four years, the IDA says. The

trouble is, desalinated water is typically more expensive than water from other

sources and, as climate scientists repeatedly warn, wet areas will become

wetter and drier regions more parched, the prospect of these costs rising seems

certain.

What can be done?

The

solution to water scarcity is largely in the hands of governments, not

companies, because it requires policies such as better regulation of irrigation

groundwater or more intelligent use of wastewater. Some states have shown how

this can be done. Israel and Singapore have water recycling and management

measures widely regarded as models. But such examples are relatively scarce and

that has led some businesses to take matters into their own hands.

A group

of companies including Nestlé and Coca-Cola has joined forces with the

International Finance Corporation, the World Bank’s private investment arm, to

form the2030 Water Resources Group,

a body trying to highlight the dimensions of the water scarcity problem and the

least costly way of tackling it. It has produced sobering reports,including one showing

demand for freshwater is likely to outstrip global supply by about 40 per cent

by 2030 unless more is done to improve supply and stop inefficient use.

But some

types of action make much more financial sense than others, according toanother report

from the group last year by Arup, the engineering consultancy. Plugging leaks

at an existing water supply system, for example, can address water scarcity 50

to 100 times more cost effectively than building an expensive water treatment

plant.

Solutions

to water scarcity, in other words, are known and do not need to be that

expensive. The risk a growing number of business leaders fear, however, is that

such steps will be deferred until the last minute, forcing a costly scramble

for action. “If we don’t tackle this water issue we are going to run out of

water,” says Nestlé’s Peter Brabeck, “and then we will start to try to make

decisions which are not always necessarily the best ones.”

No comments:

Post a Comment